Growing up, Adam Robinson always had a healthy interest in space science, and many of his heroes were astronauts. The recent St. Petersburg College graduate has co-authored an article, Haloferax volcanii in Subsurface Mars Conditions, with his SPC biology professor, Dr. Shannon Ulrich. The research, which seeks the possibility of life on Mars, is soon to be published in Astrobiology, a peer-reviewed journal focusing on new findings and discoveries from interplanetary exploration and laboratory research.

Robinson, who graduated in December 2021 with a bachelor’s degree in biology, said his curiosity for the topic began when Ulrich showed her Biology 101 class a paper outlining findings from a research project.

“It was about indications of small amounts of water being found on Mars,” Robinson said. “I didn’t know much going in, but I did a deep dive. My interest in science was only surface level until I started taking classes, then I had the opportunity to do real science for the first time.”

At the end of the semester, Ulrich challenged students to design experiments, and Robinson aimed high: He wanted to design a Mars simulation and see what might survive in that environment.

“He was really interested in life on Mars,” Ulrich said, “and seeing if we had any microbes here that would survive the simulated Mars conditions.”

This would not be a quick and inexpensive experiment – it took place over five years – but Robinson said Ulrich was quick to support him.

“When I pitched her the experiment, she sat there thinking for a second and said, ‘If we can fit it in the budget, we can make it happen.’”

Ulrich secured a Titan Grant from the SPC Foundation and scraped together some other research monies to fund the research. Robinson talked to other SPC professors, who found him some needed supplies, and one, Dr. Chris Lue, whose Ph.D. work focused on using a vacuum chamber, gave Robinson a crash course on how to build and use one to simulate Martian conditions. A University of South Florida marine science professor offered the use of her high-powered microscope and lab space. Ulrich said everyone who helped Robinson did so for the love of science as well as to cultivate a student’s interest in the field.

“So many of our students want to engage and have real research experience,” Ulrich said. “Once they get going on a project, the ownership is amazing. They’re willing to spend extra days, nights and weekends on the projects, and it’s so cool to see that passion and facilitate their needs.”

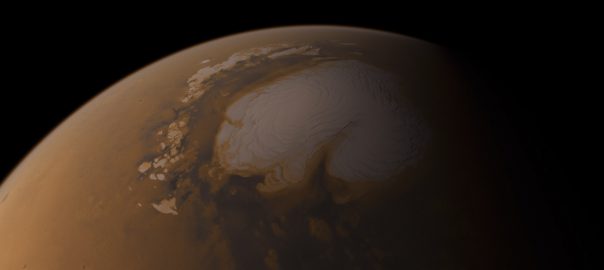

According to Ulrich, when looking for life in space, the most likely thing you’ll find would be microbes somewhere. Where liquid water exists, something could be alive there. The atmosphere on Mars is lower, carbon dioxide levels are higher, and there are high levels of radiation on its surface, along with wildly varying temperatures. All things considered, the most potentially habitable areas there would be underground aquifers. The experiment simulated underground Martian aquifers and placed organisms from Earth in those conditions to see what happens.

“The microbes survived months of exposure, showing that they are capable of surviving these simulated sub-surface Martian environments,” Ulrich said. “After 100 days, they were moved back to their optimal conditions and were still capable of growth. It’s the first time we’ve seen documented survivability of archaea in subsurface Mars-like conditions.”

Robinson said he’s now working in a lab processing COVID-19 samples, continuing his research with Ulrich, and applying to graduate schools.

“This experiment kind of snowballed from a glorified science project to a very small contribution to a field that likes to think there could be life on Mars,” he said. “My research suggests what could potentially live in the extreme environment on Mars.”